Investing Fast & Slow: background

To invest is human: investing is and will remain a cultural phenomenon that has evolved in a way which contributes to the growing role of intelligence in the universe. That evolution involves a proliferating series of tool sets to help do the job.

As each new tool has arrived, intelligent people have feared that the game is changed. (Here's how Robert Mayo, then head of the Chicago Fed discussed with the FOMC the rise of the options market in the 1970s: 'My elbow is still uneasy about this. There is a counterculture, if you want to distinguish it that formally, developing now with the evolution of puts, that will counterbalance the calls, and the market will be better again. But this is getting into real mystique. I don’t think anyone really knows what he’s talking about.')

But no matter what the technology, at both the top and bottom of the investment-decision tree, we have humans. At the bottom of the tree, we have humans making decisions about whether to invest and how to invest. Having made the decision to save, and save in equities, what governs the choice between single stocks, mutual funds, ETFs, family offices, hedge funds, or CDFs and derivatives of various kinds? Price, fashion, advice?

When an institutional vehicle is chosen, the way that institutional vehicle runs itself is constrained by irreducible human factors, including fashion, 'respectability', theoretical justification (portfolio theory etc). the regulatory environment, and the sensitivities of investors and trustees. And finally, at the top of the investment decision, the entire investment environment is affected by the decisions of the 12 people on the FOMC. History provides abundant evidence of human intelligence and fallibility in their decisions.

Essentially then, investing is a human activity, and therefore an expression of human thought.

Which brings us to Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky and the book 'Thinking, Fast and Slow'. Kahneman's book gave birth to the field of behavioural economics and in its wake there have been a large number of usually unsuccessful attempts to deploy the insights of behavioural economics (ie, loss aversion etc) into investment strategy.

But it may be more useful to consider what he has to say more widely. At the heart of 'Thinking, Fast & Slow' is the description of two types of thinking. System 1 thinking is fast thinking, what we do, very often unknowingly or instinctively, to make snap decisions about situations we encounter all the time. By contrast, System 2 thinking is slow and deliberative, demanding an expenditure of energy in conscious effort. (And System 2 thinking is expensive: as someone said, 'Most of the world's problems can be solved with five minutes thought. But thinking is hard, and five minutes is a long time.')

It strikes me that since investing is an essentially human activity, we should understand that the results will always represent a mixture between the results of System 1 thinking and System 2 thinking. And so to the Coldwater Fast Model.

Investing Fast & Slow: Coldwater Fast Model

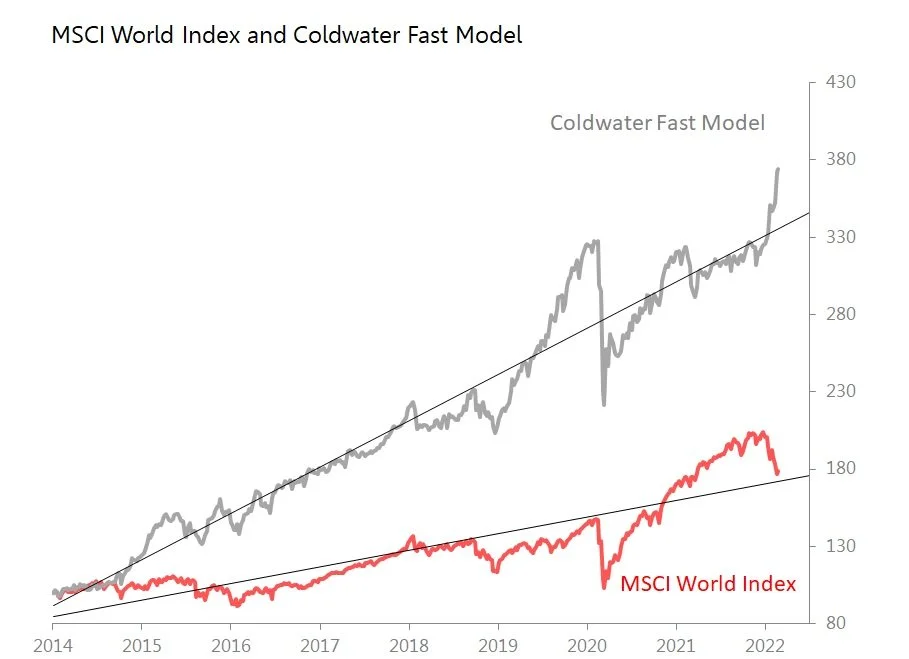

Since its inception in 2014 the Coldwater Fast Model has gained 274%, whilst the MSCI World Index has risen only 79%. The average weekly gain for the MSCI World Index during that period is 0.16%, with a standard deviation of 2.18%; the weekly average for the Coldwater Fast Model +0.34%, with a standard deviation of 2.36%%

The Coldwater Fast Model is not about chasing micro-trends before they evaporate. Rather, I chase insight into what drives System 1 thinking about investment. If a portion of market-pricing at any one time is the result of System 1 thinking, we should expect it to be the result of impressions and feeling and instincts which eventually surface as the explicit beliefs expressed in the deliberate choices of System 2 thinking.

But these impressions and feelings will not be random. To quote Kahneman System 1 type thinking 'has also learned skills . . . and understanding nuances of ... situations. Some skills . . . are acquired only by specialized experts. Others are widely shared.'

I track what generates those impressions and feelings, using as feedstocks the shocks & surprises indexes generated by my unusually broad and detailed tracking of global economic data. The very name 'shocks and surprises' conveys the hint - that these are precisely the data which System 1 type thinking is likely to notice and react to. Yet as Kahneman warns 'the automatic operations of System 1 generate surprisingly complex patterns of ideas,' and the intuitive belief that movements in asset prices will simply mimic the trajectory of shocks & surprises indexes turns out to be wrong. Such a simple interpretation will, alas, lose you money.

But further exploration has borne fruit. Alternating investment choices among the world's major stockmarkets, with a constant holdings period of two weeks using models approximating System 1 thinking has allowed a consistent and ultimately rather spectacular outperformance of the MSCI World Index since I started this at the beginning of 2014.

The choices are published to clients every Thursday, with every signal based solely on the evidence of the Coldwater Shocks & Surprises Indexes. They are, then, verifiable both in timing and underlying justification - there’s no ‘hindsight’ model-fitting at work in the results.

The results? Since that period, the MSCI World Index has gained 79%, whilst the Coldwater Fast Model has gained 274%%. The average weekly gain for the MSCI World Index during that period is 0.16%, with a standard deviation of 2.18%; the weekly average for the Coldwater Fast Model +0.34%, with a standard deviation of 2.36%%.

Conclusion? Investing Fast isn't about turning over your portfolio at rapid speed, it's about understanding that System 1 thinking is part of how market prices emerge in the short term.